At the opening we see a blackened stage before the ruins of the walls of Troy, on the beach in front of the city gates. Through the great gaps in the wall are visible the seated chorus draped in black shrouds.

A single light rises at stage front, revealing Hecuba, Queen of Troy, prostrate on the ground, wearing tatters of her royal robe and shawl. She lifts her head, asking why she still lives, and as she rises to her knees, she asks why the sea has brought her such grief. As she clenches a fist above her head, calling Helen’s name, she bemoans her lost country, children, and husband. Painfully she rises fully from the ground as lights come up behind her, to reveal a group of women in black tattered robes and shawls, who come forward, obscuring Hecuba from sight and taking over her song.

An extended chorus with soloists speaks of a dance of the grave, to the sound of weeping, to the song of never-ending tears. It describes how a four-wheeled cart brought the horse through their gates, with its deadly cargo. The dancing becomes more rhythmic and energetic, some girls playing tambourines, as they re-enact the entry of the horse into the city. The chorus describes the sacking of the city, as the dancers re-enact, in a stylized manner, what is being described. As the scene reaches its climax, the dancers assume attitudes of grief, revealing Hecuba once again, as before.

The next scene opens as the Greek messenger, Talthybius, enters with his guards; their armor is extremely primitive, almost savage, made of leather and employing no metal. While women’s voices are heard wailing throughout the following conversation, he tells the women what their fate will be, whose slave they will be, or whose concubine. Hecuba is horrified to learn that her daughter-in-law, Andromache, will be taken as a concubine by the son of the man who killed her husband, Hector, and that she herself will be a slave in the house of Odysseus, the hero who suggested the deceitful use of the sacred horse as a means of conquering Troy. Hecuba begins keening, tearing her hair and biting her hand, as she falls to the earth.

The chorus has grouped itself behind Talthybius in such a way as to obscure the rear sections of the stage. A glow as of torchlight is seen behind them. Cassandra’s voice is heard from within, over the chorus women, in a wordless vocalise. Talthybius questions the sound, but Hecuba rises, alarmed, to say it is only her daughter who has gone mad. Talthybius tells her that Cassandra has been chosen by Agamemnon, the high King, for his bed. Hecuba blocks the soldier’s way with her body, objecting that Cassandra is a virgin priestess of Apollo. Her pleas are ignored as she falls and is helped to the side by her women.

The group parts, revealing Cassandra, dishevelled and wild-eyed, her sacred white stole in tatters. She holds her arms aloft so that her open hands, palms crossed and forward, hide her face. Very slowly, she moves her hands down from her face. Two women in white tatters are with her, holding torches. Cassandra takes one of the torches and waves it about as she slowly dances in circular movement among the women, singing, in a trance-like state, of touching to fire this holy place and wails that she is blessed to lie with a king, in a king’s bed in Argos. One of the women takes the torch from her as she addresses Hecuba, her mother. She will lift high her flame, and hasten to her marriage bed in the house of the dead. As an invocation, she asks the Queen of Night to crown her triumph with wreaths and with dancing as she brings down ruin on those who destroyed Troy.

She begins to compulsively move, in an erratic dance-like motion, with hieratic movements, somewhat mysteriously, singing a dance of death. Suddenly she stops, as if her mind has cleared, and speaks to her mother, asking why has this happened. The Greek King destroyed what he loved most to retrieve what he hated. She says that they are far happier than the Greeks.

Hecuba’s voice joins Cassandra as they try to understand the meaning of their suffering. All this misery, all this horror because a man desired a woman. As Cassandra moves and sings more and more frantically and hysterically, but with conviction and triumph in her voice, she prophesies what will come to pass - the deaths of herself, Agamemnon, and the destruction of his family. Her last utterance is delivered as a scream of agony. With arms outstretched, she is led away by the soldiers.

There follows a massive chorus, demanding of a Higher Power an explanation of the fate which has befallen Troy and its people: why blood drips upon the altar-steps of Zeus, why the mighty are cast down and the free made slave, as they see the silent road by which all mortal things are led to justice.

In the next scene, Andromache, wife of the hero Hector, and their son Astyanax enter in a tumbril drawn by guards, on which stands Hector’s armor in effigy. They are greeted by Hecuba and the chorus. Andromache descends from the tumbril and helps Astyanax down. Hecuba, still on her knees, remains absorbed in her thoughts. Andromache addresses Hecuba, helping her to rise. She bursts out in anguish, clutching Astyanax to her. With shock and disbelief she describes the utter collapse of her life, its goals, and the joys she had with her noble husband and family. All that is gone and what remains is the shame of a slave in the bed of her enemy. As she weeps, Hecuba’s voice joins her in their mutual grief and bewilderment. Hecuba encourages her to use her sweet ways to help raise Astyanax to manhood, since he is the only male heir left alive of the Trojan royal house. The chorus joins with a moving lament for the memories of joys left behind.

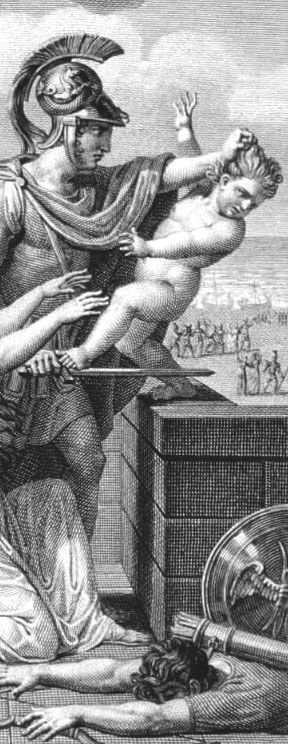

Talthybius has entered with his guards during the last part of the foregoing chorus. He now addresses Andromache. As he starts to speak of the child, Hecuba is full of foreboding. Not grasping at first what she is being told, Andromache insists they can not be separated. Talthybius hesitates, then finally says that her young son must die, to be thrown off the highest tower left standing in the city. Beginning as a low wail, gradually rising to an outburst of agony and disbelief, Andromache, Hecuba and the chorus express their horror and pain.

Talthybius advises Andromache not to resist. If she does not relent, the child will be left with no grave, given no burial. Andromache grasps Astyanax to her bosom. After a pause, during which Andromache looks steadfastly at Astyanax, at last, she addresses him. With tender feeling she tells him he must go now and die, an innocent child whose father and mother can not save from death. She asks him not to weep and to come closer and kiss her, she will never hold him again. Finally, she pushes the boy toward Talthybius, saying God has destroyed her and she can not save her own child from death. She mounts the tumbril and is immediately taken away.

Talthybius tells the boy to come with him, saying that he feels shame at having to obey such orders. Hecuba holds Astyanax, kissing him and saying goodbye. Talthybius and his guard lead the boy away. Hecuba collapses prostrate, and the chorus remains in attitudes of despair.

The next scene opens as Menelaus and his bodyguard enter. Hecuba rouses herself. Helen is being brought in under guard. At the sound of the name, Hecuba’s head rears up; her ladies and the other women group themselves as if to attack. Menelaus calls for the women with Hecuba to keep back. The Greek guards forcibly restrain the women’s mounting fury as Helen is brought in. In contrast to the other women Helen is dressed beautifully, wearing ornaments, and has carefully arranged her hair. She eyes Hecuba and the other women warily, making her way directly to Menelaus.

Her pride and arrogance infuriate Hecuba and the women of conquered Troy. Helen addresses her husband insinuatingly and seductively, asking if she is to live or die. He replies that she is to be taken to Greece to face those she has wronged and be punished. Helen asks to be allowed to speak out against the charge. Hecuba encourages Menelaus to kill her, for through men’s eyes she conquers them.

Helen, alarmed, insists she must be allowed to speak or else she will die innocent and wronged. Menelaus replies he has come to kill her, not argue with her. Hecuba steps between them and asks Menelaus to listen to Helen, then she, Hecuba will give him her answer. Menelaus agrees to let Helen speak but for Hecuba’s sake not hers.

Helen comes forward with fists clenched. Paris is to blame, Menelaus is to blame, Hecuba and Priam are to blame, not she. Even Aphrodite is to blame for blinding her eyes with the beauty of Paris. She has asked herself why did she leave her country, husband, home - she can not answer why.

Hecuba contemptuously says she will show her for the liar that she is. Yes, her son Paris was beautiful, all dressed in Trojan gold, and Helen was mad with love for him. Helen begs Menelaus not to punish her. Hecuba asks if Paris took her by force and why did she not cry out if she was abducted. Helen answers that she has been a slave in Troy, no joy, no triumph, only bitterness. From the moment she was born she had been set apart, mocked cruelly by the gift of Iife. She was Aphrodite’s gift. Her beauty has made her hideous in the eyes of the world. With sincerity and restraint, she asks that Queen Persephone hear the songs and dances of maidens, daughters of Earth, offering music for her despair with flute, pipe and string, echoing her heart’s agony, filling her emptiness.

Hecuba breaks in furiously, declaiming in a forceful manner, arms outstretched, that there was no need for Goddesses, her son had filled her mind with dreams. Stern Sparta had grown too small for her luxuries, her insolent excesses.

Helen holds her ears, refusing to listen. Hecuba removes Helen’s hands by force, declaring she will listen, she will see her own vanity and pride. Hecuba with harsh and biting words brings Helen to her knees before her as if under a tremendous weight. At last she asks Menelaus to be worthy of himself and kill Helen.

Menelaus agrees and tells Helen to go, that death is near: a death that will blot out remembrance of the face which has destroyed so many. He will take her home for punishment. Her death is far too small a price to pay for his dishonor.

Desperately and sincerely impassioned, Helen begs for her life, cursing the ship that brought Paris to her home, full of guilt at the lost lives of Troy. She is afraid to die.

Aside, an incredulous Hecuba reflects that Helen sees herself as a victim, in the same way as herself, she asks why do we so wound one another.

Helen with great passion laments the losses for Greece and Troy, but she is afraid to die. She calls Aphrodite the anchor of all her hopes. After a moment, she looks up at her husband and says that he is her anchor. Menelaus is abrupt and orders the guards to take her to his ship. Hecuba is suddenly roused from her thoughts, and insists that once a lover always a lover. Helen should die in Troy. Menelaus says in Argos her fate will be cruel, and hard as her heart.

Hecuba watches as Helen begins to raise herself slowly from the ground. She reaches out tentatively to Menelaus for help. He hesitates, as if in the clutches of internal struggle; then he helps her rise from her kneeling position. Helen, unseen by him, glances meaningfully and almost triumphantly at Hecuba. As the chorus curses Helen, their gazes remain locked as Helen is helped up, finally turns from her, bringing her eyes to Menelaus’ eyes and is escorted off on the arm of her husband. Hecuba continues to watch Helen’s departure as the chorus calls down a seastorm to fall upon the ship of Menelaus.

In the final scene, Talthybius enters with his guard, who carry the body of Astyanax on his father’s shield. In the background a group of chiIdren, chained together, are being herded toward the Greek ships. Talthybius tells Hecuba of Andromache’s last wishes: to lay little Astyanax in Hecuba’s arms only, to cover his body with whatever she has left and to bury him with flowers if she can.

As Hecuba listens, her pride before her enemies, which has served her so well, finally breaks, and she begins to weep uncontrollably. Her ladies, suddenly in alarm, press forward to support their Queen as she, keening, falls to her knees beside the broken body of her beloved grandson.

She tells Talthybius that a child has made the Greek Kings afraid. They have killed an innocent child. This is the fear which comes with war, the desire for power which drives men insane, giving license to kill, to rape, and to satisfy every animal lust which keeps us from God. She sends everyone away and turns to Astyanax’ body. The women move a little away from Hecuba.

Weeping, she bids the child goodbye and covers him with her tattered shawl. The chorus joins her lament for their dead prince. The covered body of Astyanax is carried off on Hector’s shield. Hecuba begins to strike the ground repeatedly with her hands, then raises them aloft. The women imitate her movements. They express their anger and grief at the loss of their city and their loved ones.

Trumpets sound. The women are slowly led to the ships, leaving Hecuba alone as she appeared at the beginning of the drama. She asks God, The Ancient of Days: do you see, do you hear, do you care? She calls upon Him to hear her. Everything has brought her to ask why, why, why?

She realizes that she has endured, that she still is, and her answer is that she has learned to ask God why. As the chorus bids farewell to their lost country, the lights gradually diminish until only Hecuba’s face and hands are lit, in an attitude of supplication and obeisance. She says he who asks is one with God and the Earth. She prostrates herself as at the beginning of the drama. All is darkness.

Text drawn by Erwin R. Vrooman from the libretto 2009