A Dramatic Oratorio in One Act

Not as yet performed, this offering on the website presents five excerpts, the vocal score, libretto and synthesizer transcriptions of the orchestral score by the Composer.

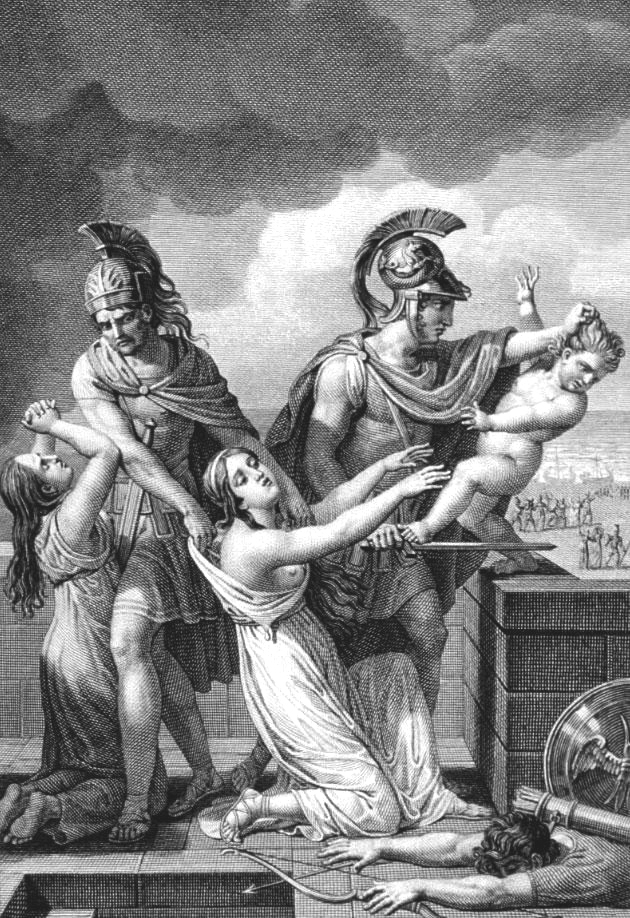

The work is based on The Trojan Women by Euripides which was first performed in 415 BC in Athens, Greece, as part of the Great Dionysia, a late spring festival of plays and artistic presentations honoring the demigod Dionysus. The play is considered to be the very first historical example of an anti-war artwork.

Originally produced during the Peloponnesian War, the play’s message was, no doubt, influenced by it, especially the brutal Athenian conquest, massacre and enslavement of the people of the island of Melos in the Aegean Sea earlier that year.

Ironically, Euripides’ play won only second prize, losing to the little known tragedian, Xenocles, but had such profound merit that it has survived through the centuries. The awarding of second place may be a telling comment on the discomfort of the judges, who may have understood Euripides’ work as a pointed moral chastisement.

The play has much to say to us in our own troubled times. Its lessons are still potent ones, as any examination of today’s continuing cruelties towards women and children will readily confirm. It also puts in sharp focus how men themselves are still taught from childhood a love of weapons, that being a man means being tough and successfully competitive, and that brutal conduct is justified, because it is War and inhumane actions against today's enemy, and the weak and defenseless, are therefore acceptable.

written by Erwin R. Vrooman, 2014

Dedication

Written with the help of God, my family and friends, in memory of Dr. Joseph Epolito,

my life-long mentor and uncle, who taught me even more by his death

than he did in his life. Thanks to all.

Frank DiGiacomo

Explanatory Notes

Notes on the Creation of the Libretto

Although the myths and legends of Greece and Greek tragedy itself had long been topics of study and interest on the part of composer Frank DiGiacomo and had indirectly influenced and infiltrated all of his work, it did not occur to the composer to base a theatrical work on a Greek-based text until his exposure in January of 1978 to two of Michael Cacoyannis’ films of the Greek tragedies: Iphigenia and The Trojan Women.

The appeal of The Trojan Women as a possibility for a libretto was obvious and immediate as it provided magnificent opportunities for four singing actresses as well as a profound and moving text which might be used as a basis for a libretto rich in symbolism and the kind of intellectual and emotional directness favored by the composer. In his mind originally, DiGiacomo immediately cast the four key roles: Hecuba, Queen of Troy would be represented by Jean Loftus; Helen of Troy, by Patti Thompson; Christine Klemperer would personify Cassandra, the Virgin Priestess, Hecuba’s daughter; and Mayda Prado as Andromache, wife of the hero Hector, son of Hecuba. The interplay and variety implicit in the roles and in their original chosen interpreters provided the composer with the discipline of writing the work from its inception for these particular singers. However, the oratorio was not performed in the composer’s lifetime and still has not been staged.

Mr. DiGiacomo had spent over three years working on the libretto for The Trojan Women and had twice reshaped the text changing its form and concept as the work progressed. He referred to it as a “dramatic oratorio” more so than as an opera. As in all Greek tragedy, it is essentially a “static” work; a work of ideas and intense inner conflict, rather than action in the contemporary sense of the term. The play itself has undergone a complete transformation in its transition to a libretto. This is best explained by the composer’s own affirmation that Euripides’ play, like many other great literary works, does not in any way need music to make its effect; therefore the oratorio illumines the story in a way totally different from Euripides’ conception. The finished libretto, as a comparison with the original play will show, uses the Greek text as a departure point to make its own statement, philosophically and emotionally. To this end the text has been altered and reshaped, adding a great deal that is original with the composer and his associate, Julian R. Pace, and several passages from Euripides’ play Helen, which deals specifically with that character.

The mold in which this work is cast reveals much about the attitude of the composer and the compositional disciplines he himself has set up. The orchestration eliminates the strings which are the mainstay of the romantic orchestra and employs a large percussion battery particularly for the choruses and extensive choreographed sections. The score is fused with rhythms and melodic tendencies common to Greek and Turkish music, as well as modern dance rhythms. A variety of orchestral and vocal colors is employed to offset the somber nature of the text and action.

The depth of perception and revelation of the human condition found in Greek mythology, and its relationship to what, for want of a better term, we call “God”, is profound. Basic truths are revealed in compIicated symbols, much as in Hebraic scripture, and conventional narratives are used as vehicles for concepts which might not otherwise be set forth comprehensibly to the audience. It was with this in mind that Frank DiGiacomo fashioned the libretto for his oratorio from the ancient texts.

written by Frank DiGiacomo with Julian R. Pace 1981,

edited by Erwin R.Vrooman 2014

Background Information on the Trojan War

Three seemingly unconnected incidents converge to bring about the enormous conflict, involving Gods and Men, called the Trojan War. Priam, King of Troy, and Hecuba, his wife, were warned by an oracle that their newborn son, Paris, would bring about their deaths and the destruction of their kingdom. They were advised to cause the infant’s death by exposure on a hillside. The baby, however, was found and raised by shepherds on Mount Ida outside the city. Concurrently, in Greece, at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (parent of Achilles who would later fight in the War and kill Hector, Andromache’s husband) where several Gods and Goddesses were in attendance, Eris, the Goddess of Discord, annoyed at not being invited to the wedding, cast a golden apple into the midst of the attendant Goddesses, inscribed “For the Fairest”. Thereupon Hera, Aphrodite and Athena each claimed it as her own, and Zeus, unwilling to decide in such a matter, sent the Goddesses to the young shepherd, Paris, on Mount Ida, to make the decision. Meanwhile, Leda, a mortal woman, gave birth to four children by the God Zeus; Clytemnestra, Castor and Pollux, and Helen. Helen grew to be a remarkably beautiful woman, a half Goddess as well. She was sought as a wife by several Greek kings, who threatened war if refused. These kings, including Agamemnon, King of Mycenae and Odysseus, King of Ithaca, all swore an oath to protect the rights of whichever of them Helen chose to marry. Her choice was Menelaus, King of Sparta and brother to Agamemnon, who then married Helen’s sister Clytemnestra.

Across the seas from Greece, in what is now Turkey, lay the city-state of Troy, fabulously wealthy and favored by the Gods, a lure for the power-hungry and aggressive Kings of Greece. And there, on the hallowed slopes of Mount Ida, the three Goddesses stood before Paris and demanded to know which was the fairest. Each tempted him with gifts to win his favor; but Aphrodite won the golden apple by promising him the most beautiful woman in the world for his own.

Paris returned to Troy, sought out his true parents’ acknowledgement, and set sail for Sparta, the home of Menelaus and Helen. Shortly after Paris’ arrival in Sparta, Menelaus departed, leaving Helen alone with Paris under Aphrodite’s all-pervading influence. The two eloped and set sail for Troy, where Helen was welcomed as Paris’ wife, but with forebodings of disaster, by Priam and Hecuba, and by their children, among them, Cassandra, the Virgin Priestess of Apollo. Cassandra had also once been desired by Zeus, but so steadfast was her dedication to Apollo that she had refused Zeus’ favors. Anyone to whom Zeus revealed himself, as he did to Cassandra, was granted unfailing prophecy, a gift he could not take back; but to punish her for having spurned him he caused no one to believe her prophecies, a situation which eventually cost Cassandra her reason. The other chiIdren of Priam and Hecuba were Polyxena, a child at the time of the War’s onset and later sacrificed on Achilles’ tomb; Hector, husband of Andromache and the most noble hero of the War; and Polites, their youngest son.

Menelaus, upon learning of his wife’s flight, enlisted the aid of the Greek Kings confederate with him in attacking Troy,which they were only too happy to do, considering the enormous gain to be won for Greece should they succeed; they did not consider that the War could last so long and cause so many deaths. The massed Greek fleet was delayed in Aulis by unfavorable winds, until Agamemnon sacrificed his eldest daughter, Iphigenia, as an offering, an act which later was to precipitate his own death at his wife’s hand, after the War’s end. The Greeks arrived at Troy expecting an easy victory, but discovered the Trojans to be an even match and their city too well fortified to be easily taken. During the ensuing siege, several great heroes were killed. Hector slew Patroclus, the lover of Achilles, most warlike of the Greeks, who then killed Hector. Paris aimed an arrow at Achilles’ heel, his only vulnerable spot, killing him in turn, all of which conspired to cause Achilles’ son Neoptolemus to claim Andromache, Hector’s widow, as a spoil of war after the city’s fall.

After a ten-year siege, the Greeks were preparing to give up the cause, when Odysseus conceived a trick by which to gain entry into Troy. The Greeks built a horse of wood large enough to hold several men, and left it in front of the city gates, withdrawing to their ships in hopes that the Trojans, seeing their preparations for departure, and knowing the horse to be sacred to Athena, benefactress of Troy, would bring the horse inside the city’s walls. The priest Laocoön and Cassandra both warned the Trojans not to bring the horse inside the walls; but Laocoön was devoured by a serpent, and Cassandra, of course, was not believed, so the horse was brought into the city. During the night the waiting Greek army took the city by surprise and put its inhabitants to the sword, all except the women and children.

Among these are: Hecuba, the Queen, who has seen her husband and her son Polites slain at Zeus’ altar and her daughter Polyxena killed as an offering upon Achilles’ tomb; Cassandra, now desired by Agamemnon as a spoil of war, helpless to prevent this sacrilege; Andromache, widow of Hector, now claimed by Achilles’ son Neoptolemus in recompense for his father’s death; Astyanax, Andromache’s little son, and one of the few surviving male children; and Helen, who has been kept under armed guard by the Greeks since the city’s fall, to protect her from the Trojans until she can be returned to her husband, Menelaus, to dispose of however he sees fit.

It is on the morning following the sack of the city that the action of the dramatic oratorio begins.

written by Frank DiGiacomo with Julian R. Pace 1981

edited by Erwin R. Vrooman 2014

Title and Copyright Information

The Trojan Women - A Dramatic Oratorio in One Act

Libretto adapted and reworked by Frank DiGiacomo and Julian R. Pace from “The Trojan Women by Euripides” by Edith Hamilton, translator, from THREE GREEK PLAYS: Prometheus Bound, Agamemnon, and The Trojan Women, translated by Edith Hamilton.

Copyright © 1937 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., renewed © 1965 by Doris Fielding Reid.

Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

and

from “Helen” by Euripides in THE BACCHAE AND OTHER PLAYS by Euripides, translated by Philip Vellacott (Penguin UK 1954, Revised 1972).

Copyright © Philip Vellacott, 1954, 1972.

Used with permission.

© Copyright 1977 Frank DiGiacomo

© Copyright 1981 Frank DiGiacomo

© Copyright 2010 Frank DiGiacomo

© Copyright 2015 Sing DiGiacomo

All Rights Reserved under applicable law worldwide.

All rights of public, theatrical, radio, television, and film performance, mechanical reproduction in any form whatsoever, translation of the libretto, of the complete oratorio or parts thereof are strictly reserved.

License to perform this work in whole or in part must be secured from Sing DiGiacomo.

Terms will be quoted upon request. Contact singdigiacomo@gmail.com with your request.

Technical Information

Characters in Order of Appearance

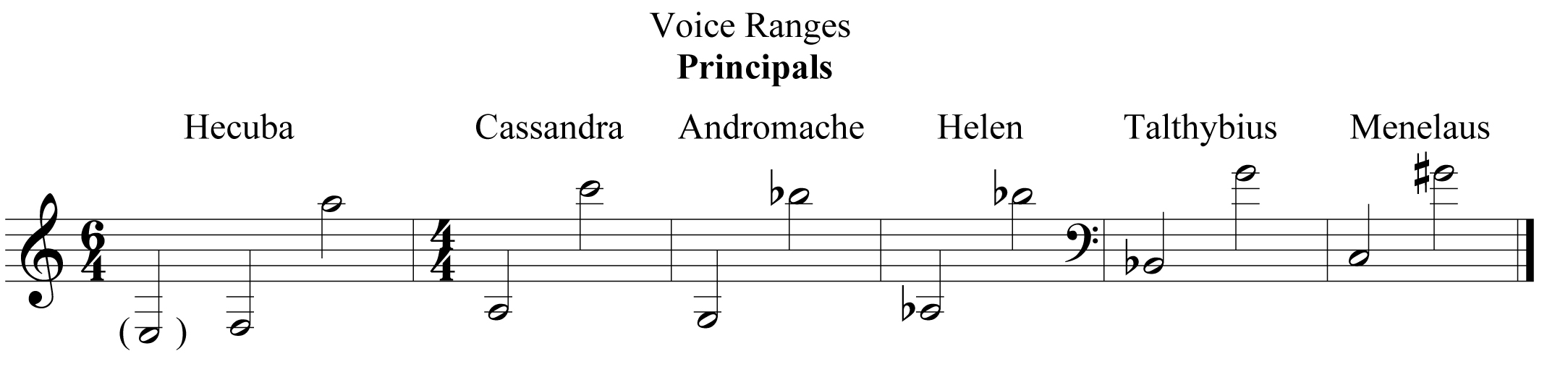

Hecuba, Queen of Troy Mezzo Soprano

Talthybius, Greek envoy to the Trojan prisoners Baritone

Cassandra, Hecuba’s daughter; virgin priestess of Apollo Soprano

Andromache, wife of Hector, Hecuba’s son Soprano

Astyanax, infant son of Andromache and Hector Silent Role

Menelaus, King of Sparta Baritone

Helen, wife of Menelaus; mistress of Hecuba’s son, Paris Soprano

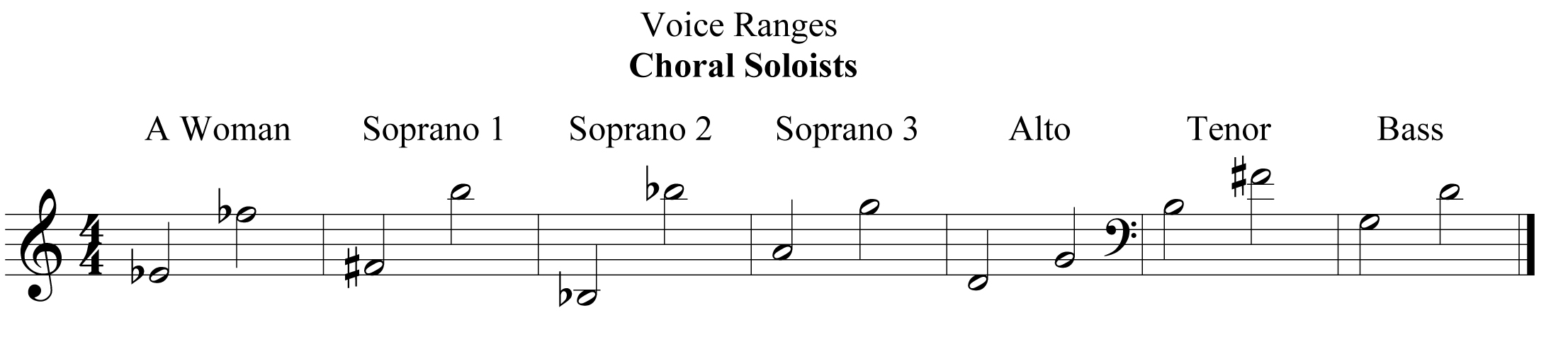

A Woman Soprano

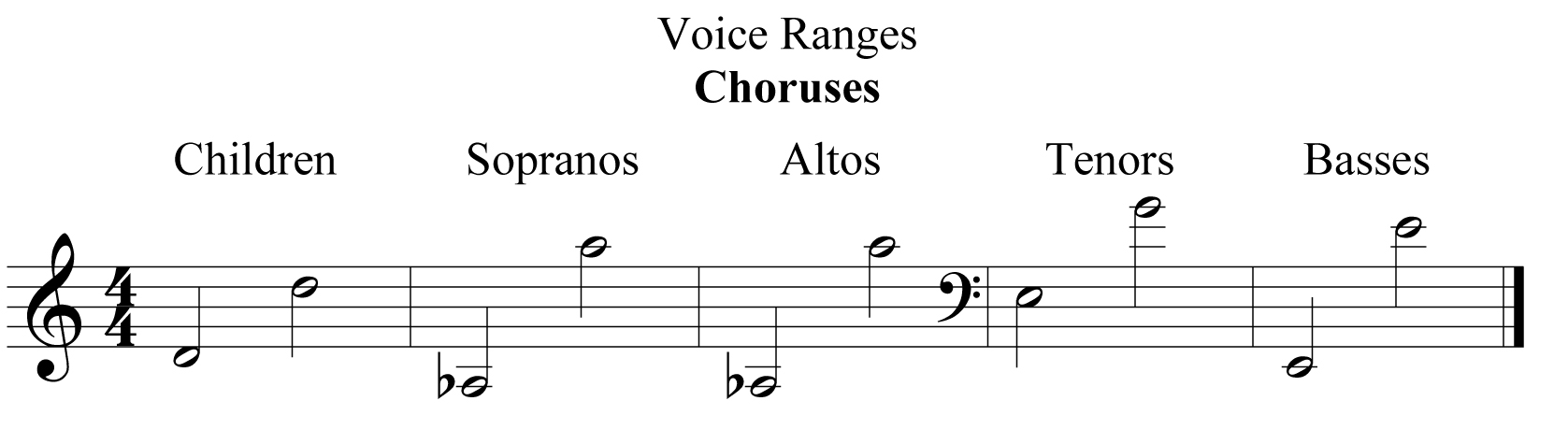

Chorus SATB

Children of Troy S

Women of Troy SA

Greek Soldiers

Orchestration

Flutes 1 and 2

Flute 3/Piccolo

Oboe

English Horn

E Flat Clarinet

B Flat Clarinets 1 and 2

Bass Clarinet

Bassoon

French Horn

Trumpets 1 and 2

Bass Trombones 1 and 2

Greek Cembalom

Harp

String Basses 1 and 2

Percussion Battery: Bass Drum, Celesta, Chimes, Conga Drums, Cowbell, Cymbals, Finger Cymbals, Glockenspiel, Gongs 1 and 2, Hand Drum, Sleighbells, Snare Drum, Tambourines 1 and 2, Triangle and Woodblock.

Voice Ranges